They do build statues of critics

Nope (2022), the concept of art criticism; Lockwood on Ferrante, Grizzutti Harrison on Didion; Boss Baby meme, Stoppard, Plath

Sometimes people don’t understand the movies. A good example of this is Jordan Peele’s Nope (2022). Because it is somewhat — somewhat! — thematically subtle, it escapes audiences who are not interested in reading for theme. Even the critics’ reviews, which are more favourable (about 80% favourable, remember, since Rotten Tomatoes does a vote-counting aggregation of reviewer scores, which is stupid, but there we go) are bad. Check this out: here’s the Rotten Tomatoes list of summarised reviews.

If you read this list you would think the film is about “our obsession with spectacle”. This is absolute fucking nonsense. Nope is about humanity’s relationship with nature. Interlocking with that theme is our relationship to each other and ourselves, and show-business is the setting for the drama (and probably the inspiration), which is a good choice when your base theme involves exploitation.

The basic failure to discern and understand this theme is why people do not understand the relevance of the chimp scene. The chimp scene functions thematically as a warning (and artistically as an ear-splitting shriek, by far the most horrible part of the movie). It is there to illustrate the consequences of hubristically taking a wild animal, a sentient being we ought to understand as equal to us, and trapping and abusing and exploiting it and caring little for its needs until — in this case, via a sensory overload — it inevitably becomes violent against us. The chimp scene also lays out the path for the entire movie, because the only way to survive the chimp’s wrath is to engage with the animal on its terms, as an equal.

The film is therefore being intentionally, heavily ironic when the only survivor of the chimp scene, Jupe (Stephen Yeun), later perishes for making the mistake that all the adults around him made when he was a child: of treating other beings, whom we should approach at least with care if not with reverence, as a resource to be exploited. And yeah okay maybe there’s something in here kind of about spectacle, but it’s as much about commodity as spectacle — or more about commodity, let’s say, since OJ (Daniel Kaluuya) and the gang aren’t above spectacle but their refusal to commodify the creature whom they call Jean Jacket is the thing that sets them apart.

Is this theme difficult to read? I don’t think so. Maybe the Bible verse epigraph is confusing — I think people are grabbing onto the word “spectacle” there — but Nahum 3:6 is about being destroyed by god for the sins of greed and commodification. I think it would be possible to replace god here with nature itself and loop the theme around that way, though that might be trying to be a bit too cute (on my part).

We do see a lot of mistreatment and commodification of horses in the early scenes, with OJ acting as best he can as their defender. The film also shows the human systems that encourage this, and the human consequences: OJ’s deferential and kind nature is shown to be disadvantageous to him in show business; his sister, Emerald, played to perfection by Kiki Palmer (though she does not eclipse him, and Kaluuya is the heart of the film), has to swagger in with her brash ego and handle the Hollywood system. But out in nature, it’s OJ’s approach that works.

In fact the film outright explains this to us by having OJ just literally say it. Emerald says, of their troubles with Jean Jacket, well, we pissed it off. Otis says: “We’re not the reason it settled down. That was Jupe. He got caught up tryin’ to tame a predator. You can’t do that. You gotta enter an agreement with one.”

Is that subtle? Candice Frederick, in her review, asks “Like, why does looking up at the thing lead to a person’s demise?” There is a clear answer in the film, but to get that answer requires you to read thematically. Looking directly up at the thing is insufficiently deferential. It is not humble; it does not show the proper amount of respect. It’s again almost literally what OJ outright says.

The atmosphere of Nope is ominous and creepy and funny and delightful. I am sure I will remember Michael Wincott’s gravelly rendition of Flying Purple People Eater for the rest of my natural life. Also, we are seriously sleeping on Brandon Perea as (the) Angel. And it feels to me like an honest film. Peele is engaging in explicit commentary on systems that exploit and commodify people and animals and to some extent the rest of the natural world. Brashness and disrespect may be rewarded in certain eras, in certain industries, at certain times and places. That is true. But there will always be untameable aspects of our lives, inside our houses and out of them, and that stuff must be approached with care and caution, for that stuff will always be dangerous. Whether you want to know it or not, whether you’re insulated from it in daily life or not, there are things on this planet that eat you. Never, ever forget it.

Okay, pause. What we have got so far here is film criticism. Amateur film criticism — I do my best! — but film criticism nonetheless. I don’t know shit about cinematography or whatever so you’re not going to get any of that out of me, but I understand how to read theme in art. I share my thoughts with you because I believe it will enhance your experience of Nope when you next view it, and improve (in some small way, at least, among us) the cultural understanding and reception of it, and thereby — through all of that — I think — improve the culture.

But what if I didn’t like it? Would it be wrong to say? Would that not be a way to improve things? Would it be bad or mean or demonstrative of some essential deficiency in me if I wanted to share with you reasons why I didn’t like something? Is negative criticism so wrong, such outright evidence of lack? Some artists and writers seem to think so. You can hear a lot of commentary on the commentary that essentially wishes that art critics would simply go away. You can even see musicians wearing t-shirts that say “they don’t build statues of critics”.

Really what these people object to is that sometimes critics don’t like their art, but it feels too childish to say that, so instead they have to take this garbled approach wherein suddenly all commentary is suspect. The critic contributes nothing, according to this schema, he is a parasite, his very role is evidence only of his own frustration and inadequacy, and nobody likes him, and he really does nothing at all.

Does that sound right to you? It doesn’t sound right to me. There’s at least one problem with all that just on the surface: They do. They do build statues of critics.

***

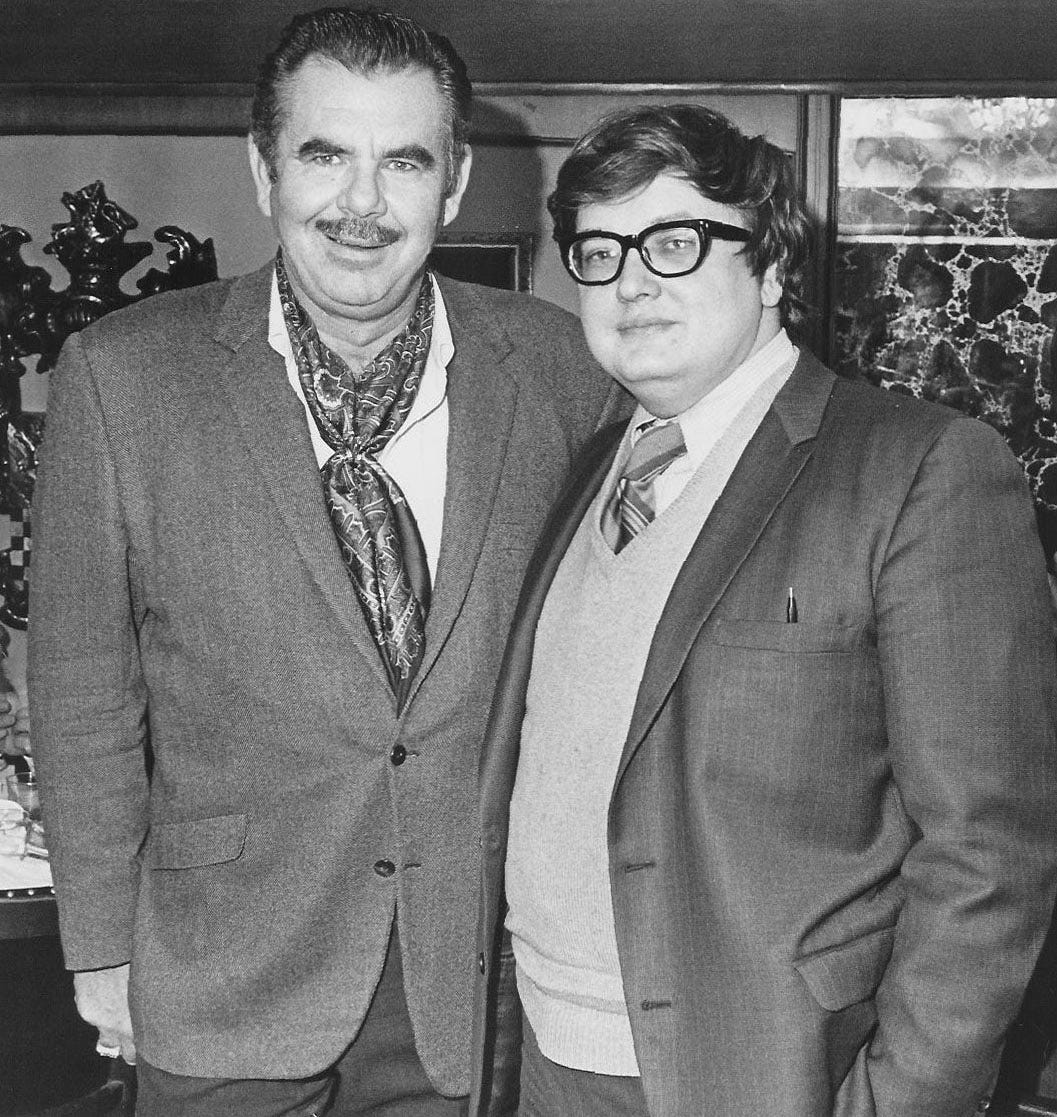

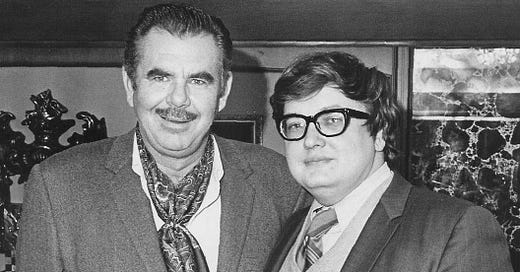

Who else can we start with but Roger Ebert? As critics go, he is the people’s princess. And the people built a statue of him in Champaign, Illinois, one town over from his native Urbana — a testament to the good taste of Ebert himself and of Illinoians (Illinoiers?). In Champaign apparently they even have a film festival called Ebertfest, which is devoted to supporting films deemed underrated and overlooked.

It’s not hard to love that. Who doesn’t love that? But of course Roger Ebert also gave bad reviews to what he considered bad films, that’s what it means to be a film critic and a person, you can’t love or even like everything no matter how hard you try; and why try to, this is real life, things and people can fail to deliver what they attempt, or attempt to deliver something that would be very wrong and bad to do. Roger Ebert dot com still provides many negative reviews. People still read it and love it.

The irony here is that criticism is a popular medium. Newspapers and magazines still hire critics even in the collapsing media landscape or whatever is going on. The legendary Australian art critic Robert Hughes was trying to become a novelist when the world demanded he become a fucking fine art critic. People want art criticism more than they want novels!1

And I don’t think that’s just because the public is a bunch of frustrated artists who want to see a critic draw blood on the brave warriors of the creative spirit or whatever else the artists want to say is going on here. No, come on, there’s an obvious direct-to-consumer function here which is that there’s too many movies to see and books to read and gallery shows to go to than any of us could see or read or trot through in one lifetime. So we need help deciding. And then art can be challenging! Or not challenging, as the case may be, not challenging when it should be! And then after people see art they want to know what other people thought — there’s bad reasons for that, like to shirk the responsibility of their own taste-making, but there’s also good reasons for that, like to broaden one’s own palate at least of understanding if not of taste, to connect with art more fully, and to connect with others who may think differently to ourselves. But that’s not easy! That’s never easy. So I think people like and care about critics for the same reason people like and care about the dictionary: we need help to talk about stuff.

It’s not my intention to provide a history of criticism nor even a complete defence of it, neither of which I would be capable of delivering. And in my partial defence of criticism I am not defending the majority of critics or critical writing — it is bad, like the majority of everything (this is one of a few common themes emerging from this newsletter). Nor do I think it is necessarily bad in a manner pure and accidental. I know nothing about the history or practice of criticism but I imagine it’s as warped and sordid as anything else, and this excellent piece by Julian Barnes about Monet in the LRB suggests that it certainly is.

So now we’ve come to the real reason for my writing this piece: the LRB. I love the LRB beyond reason. To the extent that there is any ritual in my life it is that I crack open every issue of the LRB and see what catches my attention.2

How to explain what is so good and beautiful about it? Let’s start with Patricia Lockwood. Those of you that are too online might do a double take here: Patricia Lockwood? Patricia Lockwood of “you KICK Miette?”! The very same. In case you, like me, have trouble ever logging off twitter, it might surprise you to learn that Patricia Lockwood is in fact an author and literary critic and she is a very, very good one. Consider, for example, her essay on Elena Ferrante, wonderfully titled: “I hate Nadia beyond reason”.

It’s ostensibly a book review of The Lying Life of Adults, but it’s more than that, and you’ll know it immediately, since it begins like this:

“Do you understand what a pleasure it is not to have to begin with this little biographical section? Sometimes a writer goes to school somewhere, and you have to know which years. Sometimes a writer gets married three times, or is a sex freak, or stabs people at parties. The cry BUT WE DON’T KNOW WHO ELENA FERRANTE IS, EXCEPT FOR THOSE OF US WHO LOOKED UP HER REAL ESTATE RECORDS! is met from me only with the words: ‘Thank God.’ I am tired of knowing who people are.”

First of all, this is outstanding writing. It’s subtle enough that it does not draw attention, but this writing immediately grabs and holds you close, and then it plunges you into the experience of being a person who is not you, who is Lockwood. And I love it that she starts head-on like a battering ram at the door of the first complaint, waaaah, how can we read your novels if we don’t know what you looooook liiiiike, we don’t want to know your art if we can’t know who you aaaaaaare.

As the piece then swiftly points out, the most important thing we do not know about Ferrante, according to our own sensibility, is her — his, their, xier — gender. Lockwood skewers us for that preoccupation, quoting an incredible write-in from a Ferrante reader that first insisted she must be a woman, then parried herself with the thought that she might be a man, then abruptly concluded “Congratulations, in any case!”, a tripartite narrative of such energy and confusion that it sums up Lockwood’s own feelings on gender in the aggregate.

This is basically Lockwood telling us to stop being so fucking stupid about Elena Ferrante and start being smart and serious. I love that. This piece does what I think is the most deeply important thing criticism can do: it explains which ways of talking about a certain piece of art make sense and which do not. It’s an experience about an experience about an experience; the first experience is whatever happened to and within Ferrante which generates the novels, the second experience is the art itself as we receive it, and the third experience is the criticism as we receive that. At any point in the chain we can stumble and fall and be wrong. As a result, here is my favourite passage, discussing how often people describe Ferrante’s work as fundamentally about “friendship”:

“To call the Neapolitan Quartet ‘a rich portrait of a friendship’ seems insane, or like something a pod person would say. Lila is a demon of inducement, the cattle prod that drives the mild herd forward, Lenù the definition of homeostasis. The epigraph is from Faust, which I guess according to this formula is a story about two dudes hanging out: only one of them is completely red, because he is the Devil.”

Only one of them is completely red!!!!! Because !!!! He is the Devil!!!!!!

Lockwood also has an incredible piece on Nabokov that features a “Nabokov Bingo Card”, presumably of her own creation, that has to be seen to be believed.3 I think that until you read that piece you will not believe that it is possible to talk about Nabokov in that way — she is actually expanding our cultural vocabulary. And the LRB is full of stuff like that! Insanely good criticism of every genre and flavour. (They also do journalism and poetry!). Here is Clare Bucknell, for example, offering a fresh take on Lord Byron. No drawn-out discussion of the culture war, all facts. Killer.

Adam Mars-Jones has become another favourite of mine in recent years, where for example in reviewing Damon Galgut’s novel “The Promise” he teaches us a masterclass on novel writing, including such wisdom as: “A theme of incest between otherwise celibate siblings needs either to be developed with enormous dexterity or scrapped.” Excuse me Adam! I didn’t realise the former was an option! I will keep that in mind!!!

***

Here we start to find the rub. Is it okay for a critic to tell a novelist what he can and cannot do?

Yes. The reason for that is that art, because it is about experience, is bound by the deep fundamental laws of emotion that it cannot transgress without failing as art. The problem is that these laws are not often recognised as real and, even when we begin to recognise them and sense their presence, we find that they are profoundly non-obvious. For example, I can go no further in discussing this directly here, as these elements are virtually impossible to articulate.

What is Mars-Jones saying above? Is he saying “you’re not allowed to have a shallow side-plot about incest between otherwise celibate siblings because I don’t like it”? No, he’s saying it won’t work. The theme is too strong, it demands too much attention. It would be like introducing a side plot about Darcy running an opium-smuggling ring into Pride and Prejudice. It would overwhelm the main plot, and if for example this deranged alt-universe Austen had been determined to include it, she would have had to yield to this logic: the work would change, the work would have to change.

The attention, affection and emotional sensibility of the audience always presents any artist (writer, filmmaker, etc) with a constraint. That constraint can be negotiated with, to some extent, by an application of great artistic determination and talent, but even so at a certain point one comes to the hard limit. Beyond this point it is necessary to yield. Art, like life and nature, has a powerful internal logic; there are transgressions it does not tolerate. Not everything you can think of works. You can refuse to recognise that, of course. But you can’t stop the rest of us from noticing.

I learned a lot from the review of The Promise even though I do not necessarily intend to read the book. Mars-Jones is being critical, above, in the most quintessential sense. But is he being harsh, or unfair, or driving an agenda? Is he being mean? Not really. He’s being honest about his experience of art, and he’s highly qualified to discourse on that experience, because he writes and reads for a living, and he does so with a dedication that would make any amateur effort equivalent. (One doesn’t need to be paid to be qualified, and professional critics can also be bad, as discussed.)

But— well — here we are again — what about being mean? Is it okay to be mean? (I ask myself this a lot.) One wants to say of course no, that’s the safe answer, but that deep internal logic of the heart says yes, there must be a way in which the answer is yes. There are times when the authentic reaction to a particular experience is meanness. It’s not nice, sure. But some experiences don’t provoke one to be nice.

Consider, for example, Joan Didion.

Possibly the most beloved female essayist after Sontag or maybe not even after Sontag at all, actually. People looooove Didion. But I never have, and still don’t. I’ve never even been able to choke down a full chapter of any of her books. I just don’t like it. I don’t find a there there. It’s like reading around a void. And I sort of wandered the art landscape alone in that until I stumbled across this outstanding piece of what can only be described as take-down literary criticism, an essay by the writer and aid worker Barbara Grizzutti Harrison, which gave me the great and profound gift of finally understanding my own antipathy, and explaining my own experience back to me. Maybe nothing is more characteristic of art than this. The review itself is art. When I find it, it finds me; less alone.

Here’s how it opens:

“When I am asked why I do not find Joan Didion appealing, I am tempted to answer -- not entirely facetiously -- that my charity does not naturally extend itself to someone whose lavender love seats match exactly the potted orchids on her mantel, someone who has porcelain elephant end tables, someone who has chosen to burden her daughter with the name Quintana Roo; I am disinclined to find endearing a chronicler of the 1960s who is beset by migraines that can be triggered by her decorator's having pleated instead of gathered her new diningroom curtains. These, and other assorted facts -- such as the fact that Didion chose to buy the dress Linda Kasabian wore at the Manson trial at I. Magnin in Beverly Hills -- put me more in mind of a neurasthenic Cher than of a writer who has been called America's finest woman prose stylist. (Thinking of Didion's drapes, it occurred to me that in the worst of all possible worlds, Franny Glass might have grown up to be Maria Wyeth of Play It As It Lays. Her faith in the Jesus Prayer permanently misplaced, and possessed of no secular equivalent to fill the vacuum, in her second incarnation Franny is Maria, a fragile madonna of acedia and anomie. This feeling was confirmed when I reread all of Didion, an activity that, trust me, is roughly akin to spending several days in the company of Job's comforters.)”

A neurasthenic Cher!!! A NEURASTHENIC CHER??? Why did I have to look up “neurasthenic” to read this book review? Why did that improve my whole life?

A little further in, and I am totally obsessed with this critique of Didion’s style:

“Didion's "style" is a bag of tricks. Some of the effects she produces are quite pretty, even momentarily beautiful. But make no mistake: these are tricks -- techniques -- that can be learned (I don't know why they have evoked so much wonder). If, for example, I put Al Capone and sweet williams in the same sentence, I can be fairly sure that a certain number of readers will be jolted by the juxtaposition -- their eyes will cross, and they will assume that they are in the presence of genius. They will be wrong, of course, because unless I use this technique to draw them into meaning, I will have cheated them: a magician can pull a rabbit out of a hat and get away with it; a writer's job is to tell us what the rabbit was doing in the hat in the first place. And, as Didion will gladly acknowledge, she is interested only in the what (the "empirical evidence"), not in the why.”

It’s true. Tell me it’s not true! To argue back one has to argue that Grizzutti Harrison is wrong to say that Didion does not draw readers into meaning — that is, her overarching point about the valid use of style is evidently right, and her argument is so powerful that you would be forced to rebut it on its own terms, should you try. And woe betide you should you try: the remainder of the essay is used primarily to make this case, that Didion eschews meaning as much as humanly possible, self-distracted always by bright surfaces, ephemera, and for that reason so beloved by men. Harsh, but, I’m going to call it, fair.

Here’s a passage trying to say in 1980 something that we are still struggling with how to say 44 years on:

“"Of course," Didion says, pandering to our worst instincts, our careless and selfish desires for political quietude, "we would all like to 'believe' in something, like to assuage our private guilts in public causes, like to lose our tiresome selves." The essay in which that sentence appears was written in 1965: Vietnam. In 1965 Didion told us that "all the ad hoc committees, all the picket lines, all the brave signatures in The New York Times . . . do not confer upon anyone any ipso facto virtue." Well, whoever said they did? Believing as I do in original sin, I am not so crazed or so simple-minded as to believe that human nature can be redeemed by an act of Congress; but I also believe that the consequences of not acting are as drastic as the consequences of acting: one marched because it was right and fitting to do so, and one allowed Providence to handle the rest.”

But the essay is (unfortunately?) at its best when it is mean. When I first wrote this essay I did not want to include this following passage because I thought it was too mean and you would all turn against me and Grizzutti Harrison if I shared it and said it was good:

“For Didion, all "pain-killers" -- heroin, God, the march on Selma, the gin and hot water and Dexedrine she guzzles to write her deflating essays -- are alike. They are, she tells us, alike, but clearly she finds -- and we are meant to find -- her own pain, and her own methods of alleviating her own pain, far more consequential and lovable than those of others.”

But it is good! It’s mean, but it’s real. So that mean sentiment has value. I don’t like Didion; if I inhabit a world where everyone else likes Didion then I feel relentlessly alone. Art is how we speak to each other. It doesn’t feel good to hear nothing, or hear painful and alienating things when others are speaking. To speak up and say “I heard nothing!” is to make a bid for connection with others who hear nothing as well.

Maybe you still like Didion. Maybe that essay doesn’t tell us much except that those of us inclined to become development economists or aid workers are not going to find much of value in Didion. But that’s still something. That’s also what makes the discussions of emotional life and emotional artistic logic difficult. We are different. Not infinitely different, perhaps. But different.

Should we explicate that difference when it involves being mean about other people’s art? Is this piece an attack on Joan Didion as a person? Is it trying to squash her out of existence? It might feel like it, if you are sufficiently confused as to consider what you write in your essays to be your essential self, but the true answer is, no, of course not. This is not Didion herself. This is her work. Art is work. And work can be good or bad, it can succeed or fail. Work can be criticised. All work has standards.

***

I think some people feel — certainly it seems some artists feel — that their writing or art is above criticism because it is vulnerable and brave to make art or otherwise to put yourself out there. I actually think there is something to this, but it does not cover all art and certainly not to the same extent. Complex, demanding art about difficult topics is more vulnerable to a suppressive, reactionary response in the culture, and deserves a lighter, defter touch in pointing out its errors as a result. When such art is out in the public sphere, indeed, it is vulnerable. But to say that therefore it should not be discussed and criticised is wrong4. And to try to extend this to all art and say that it should not be negatively criticised is an ouroboric type of confusion. To the extent that all art is vulnerable and brave to make, that is only because you might fail and/or get criticised. If you demand to be sheltered from criticism then you are not being quite so brave after all.

Another strain of artistic objections to criticism is based on the notion that we should be careful with people’s feelings, and art that they make based on their feelings. I do think we should be careful with people’s feelings, but to say this means we can’t be mean or do art criticism is also a confusion — this time, about the purpose of the public versus private spheres.

We are living in a time of deep confusion about both the nature and demarcation of public life and culture on the one hand, and our intimate personal lives on the other. (I do not think this is necessarily worse, though, than when the border was so rigid that it was not possible to feel any confusion.) I do think it is easy to forget, for us, that people bound together in a private, personal sphere owe more to each other, including more consideration for one another’s feelings, than strangers owe one another in the culture. It is not right to give art criticism if somebody sings you a song or makes you a birthday card. There are also liminal spaces between private and public, like small but porous creator communities, which evolve their own norms around criticism to suit their own needs. One would not go off about how poor one’s neighbour’s work was in one’s pottery class, nor should one think that a friend’s erotic fanfiction tucked away on the AO3 demands rigorous criticism or indeed any kind of cultural response. But if someone makes a bid for their art to be part of broader public life, and enters it into “the culture”, the shared environment to which we are all ambiently exposed and thereby shaped if only just in passing, then that art not just submits to but requires and demands critique. Art criticism is a part of the cultural ecosystem.

Even if in general our feelings are valid, that in itself does not make them valid or successful as art. It is entirely possible for you to express your feelings poorly or even outright wrong in art (also in life actually!). And if you do, your art is bad, and I am afraid that if it is bad and also popular then we will have to criticise it to prevent us going insane.

But also it is possible to have the wrong feelings.5 They are still valid, like, for you, perhaps, (I think so), but they are wrong in the aggregate, so then you are wrong if you try to make big art about them, art that transfers or projects your feelings onto everybody else. Think of Sylvia Plath’s line “Every woman adores a fascist” … these are the wrong feelings Sylvia. Summon your disgust! All that misery and hallucinated Auschwitz shit, where is the fucking disgust!! OK OK CALM DOWN EVERYBODY I AM NOT SAYING YOU CANT MAKE ART ABOUT HOW PEOPLE CAN GET HOT FOR FASCISM OR DEATH OR OPPRESSION OR ANYTHING OF COURSE YOU CAN AND SHOULD I am just SAYING that if you do, you are by definition wading into territory where humans are notoriously at risk of feeling wrong, and that’s itself kind of the point. If you’re going to go there, you have to keep your wits about you. To produce anything worth adding to the culture about this, you need to be on top of your game completely, and in form like you would not believe6. (Jeremy O Harris does it.) There are areas of human feeling where you have to tread carefully. Fascism is one of them. This is not just true for moral reasons but also for artistic ones. Too much thrall to fascism, too little clarity, and we are circling a void or a drain very quickly. Entanglement with fascism is one of very, very few things that poisons the mycelium from which we can make art.

Speaking of Plath’s “Daddy”, to be honest, I probably would not invoke a genocide I was not affected by as a literary tool if I could help it. It surprises me how little criticsm there is of the poem along these lines. But I also kind of get it. It’s terrifying to criticise someone’s art when she makes it and then kills herself. Unfortunately I think the art is bad. It does not work because it is not sufficiently honest; it processes too little, it exteriorises the experience too much. Plath often makes the mistake of assuming her struggle is universal, which is also why it feels natural to her to make use of the holocaust. If she made art about the truth, about the real encoded observation of her life that poem springs from — if she said I want to fuck my abuser-tyrant father-husband, not that everybody on the planet shares my affliction — that would then be more powerful, more vulnerable, and more honest; better art. It would become more universal that way and I would defend it. To start out from the assumption that everyone is in hopeless thrall to their own destruction is a dodge, a way of avoiding the engagement with specifics, but engagement with specifics is the slab foundation on which all good art is built. So this assumption affects her art very negatively, though not as negatively as it impacted her life.

If you are wondering whether I feel nervous criticising Plath and Didion in the same blog post, especially in such strong terms, yes I’m fucking nervous. This is why I don’t really buy that criticism is risk-free, unless I suppose you pander to dominant taste. But art can pander to dominant taste too, and de-risk itself that way also. Maybe commentary is inherently safer than creating something intended to stand alone, wholesale and sincere. Maybe? Maybe. But it’s not safe.

***

The other reason why we need art criticism is that readers or consumers of art often do not have the context they would need to understand it correctly — indeed, I said correctly. That’s what prompts the Boss Baby meme. Half the reason young people and Americans in general think JK Rowling is a genius is because they do not understand how much of what is in Harry Potter already readily existed English children’s books and for that matter in England. They think she invented train stations and boarding school.

This is a persistent problem in literature, particularly in science fiction, where innovation is inherently desired by the genre. If you want to understand whether something is innovative, you have to know the history of science fiction and probably also science. But you have a full time job doing something other than knowing the history of science fiction and science. So, that’s what a critic is for: preventing or mitigating context collapse. This could hardly be more needed.

But no one critic will know everything. We all have different pieces of the context. We all bring pieces of the puzzle to the table and only if we all speak up — about our likes and dislikes as well — will we be able to assemble the picture.

Even if you think you understand something, an informed and generous critic can help you understand the work you see more fully. Here is an example. Tom Stoppard’s (relatively) new play Leopoldstadt is about the history of a Jewish family split up pre-World War 2. Some of the family stay in Austria, some choose to move to England. The family is almost entirely destroyed by the holocaust. At a certain point, the play moves to focus on the younger generation, the children of those who were adults during the war. One of these younger English cousins visits his surviving family in Austria, who are none too impressed by his tale of wartime suffering. Fed up with the lack of friendliness from one of his Austrian cousins of similar age, the English young man says, look here, my mother died in the blitz. His cousin looks at him for a moment and then repeats in a high, whining, self-aggrandising voice: “Oooeeeooh, my mother died in the blitz~~~!!!”

Of course this moment stands incredibly strongly by itself. But wouldn’t you like to know that the English cousin is meant to conjure Stoppard himself, the author of the play? Tom Stoppard was born Tomáš Sträussler, the son of a non-observant jewish family in Zlin. Though it was his father who died in the war, not his mother, and he was in a Japanese internment camp, not the English countryside, the family later settled in England and the character is clearly drawn from him. Does that not change your feelings?

Perhaps not, as it need not, or perhaps only a little — I am not saying we need to know the identity of people who make art, I promise you, far from it — but I do think that in this case it makes it not just shocking and darkly funny, which it is in and of itself, but also beautiful and quietly expansive. That moment of outrageous dialogue is Stoppard allowing us to laugh with him at himself, even at his own extremely real and haunting pain. To know that backstory is to know that this is serious, but also generous and tender. I really really like to know that stuff. But how the fuck would you know that stuff if nobody has told you? The play doesn’t have a bunch of footnotes to explain itself and nor should it. That’s also what a critic’s role is for.

The last thing I want to say is this: people get pissed off when they think criticism is gatekeeping. It isn’t. People will really call anything gatekeeping. Some random on the internet says “YA isnt real literature” and people call it “gatekeeping” it’s not!!!! It’s a diss! That’s an entirely different thing! Studio executives are gatekeeping. Publishers are gatekeeping. Grad schools and academic journals do gatekeeping. Let’s set aside whether anything is all that wrong with gatekeeping (or perhaps is it bad gatekeeping that is bad). By the time art is critiqued it is usually well past the gate.

So there you have my totally incomplete defence of criticism of literature and art. Criticism could tell you more about where the art you love, or don’t love, came from — or it could tell you why it doesn’t matter where it came from and you’re being basic for wanting to know. It could give you more context for why the thing you hate is actually good, or why the thing you don’t understand is actually legible, and to whom, and how, and why. Or it could tell you that you’ve been easily fooled by cheap artistic tricks, and show you where the rabbit goes into the hat. It connects you to others, and to your own opinions, and it opens your mind to new perspectives as well. As such it is fundamentally itself a form of art. It can be good or bad like anything, but it is an essential part of our culture. As long as there is art, there will be critics and criticism. People will always want them. Life always finds a way.

***

I am being only slightly facetious, since of course it’s possible that Hughes specifically would simply have been a terrible novelist and everyone knew it, but the point is that not since the time of Dickens has a periodical hired a novelist to write novels. If that is not true please correct me! (Ed: I stand corrected, see the comments!)

During the year and a half that I was a digital nomad wandering solo over the world the hardest thing to give up about a home was my physical LRB subscription (a chilling indictment of the overall situation of my life perhaps but, unfortunately, true).

I was going to link you to the bingo card but in true Nabokovian fashion I have decided that would be too easy, and instead you must earn the bingo card by clicking through and at the very least doing some scrolling.

What happened to Isabel Fall was not literary criticism, it was this reactive suppression.

I need you all to realise how terrifying it is to write shit like this lmao.

I’m not necessarily saying Daddy doesn’t add to the culture but it’s very, very fucking close.

I feel like an ass making my first comment here a correction, but I'll console myself with the fact that you asked. Tales of the City was serialized, at least the first few novels were, in the San Francisco Chronicle. My sense is that this fact worked against its literary reputation at first because it was considered low brow to appear in a newspaper. This could be the exception that proves the rule, as I can't come up with another example. Love everything you have published here. Thank you.

Killer! The position of the critic feels washed out in some places at the minute, so this is a refreshing read. Been thinking a lot about the cry to 'let people enjoy things', particularly in relation to Rowling when the thing itself is not very good regardless of how we understand her. If everyone is playing the game of 'I'm baby' (I signal my vulnerabilities as a way to protect myself from reasonable critique rather than bring nuance and humanity to my work) then who's flying the plane (resisting context collapse). The point in this piece where I felt real resistance was the use of train rather than railway station - take that as you will.