Presented pretty much in the order I thought of them:

The iPod

The dvd

Microform

Microfiche

The gameboy

Floppy discs

CDs

USB sticks (disputed)

The fax machine

Steam power

Filament lightbulbs (pre-emptively)

Physical film

Super Nintendo

Yo-yos

American democracy (speculative)1

Hard candy

Telegrams

Landlines in homes

Trench warfare

The harpsichord

The British empire

Henry Kissinger

Tony Bourdain

The ancient artefacts of Palmyra and Homs

The gumball machine

Personal written correspondence on paper (physical letters)

Bloodletting

Pokémon cards

Mechanical clocks

Sail power

Betamax

Metal-backed currency

Majority of humanity engaged in agriculture

The slide rule

The astrolabe

The calling card

Steve Jobs

The USSR

Smallpox

The moa

Boeing (probably)

Punk music

Orchestral music outside of cinema scores

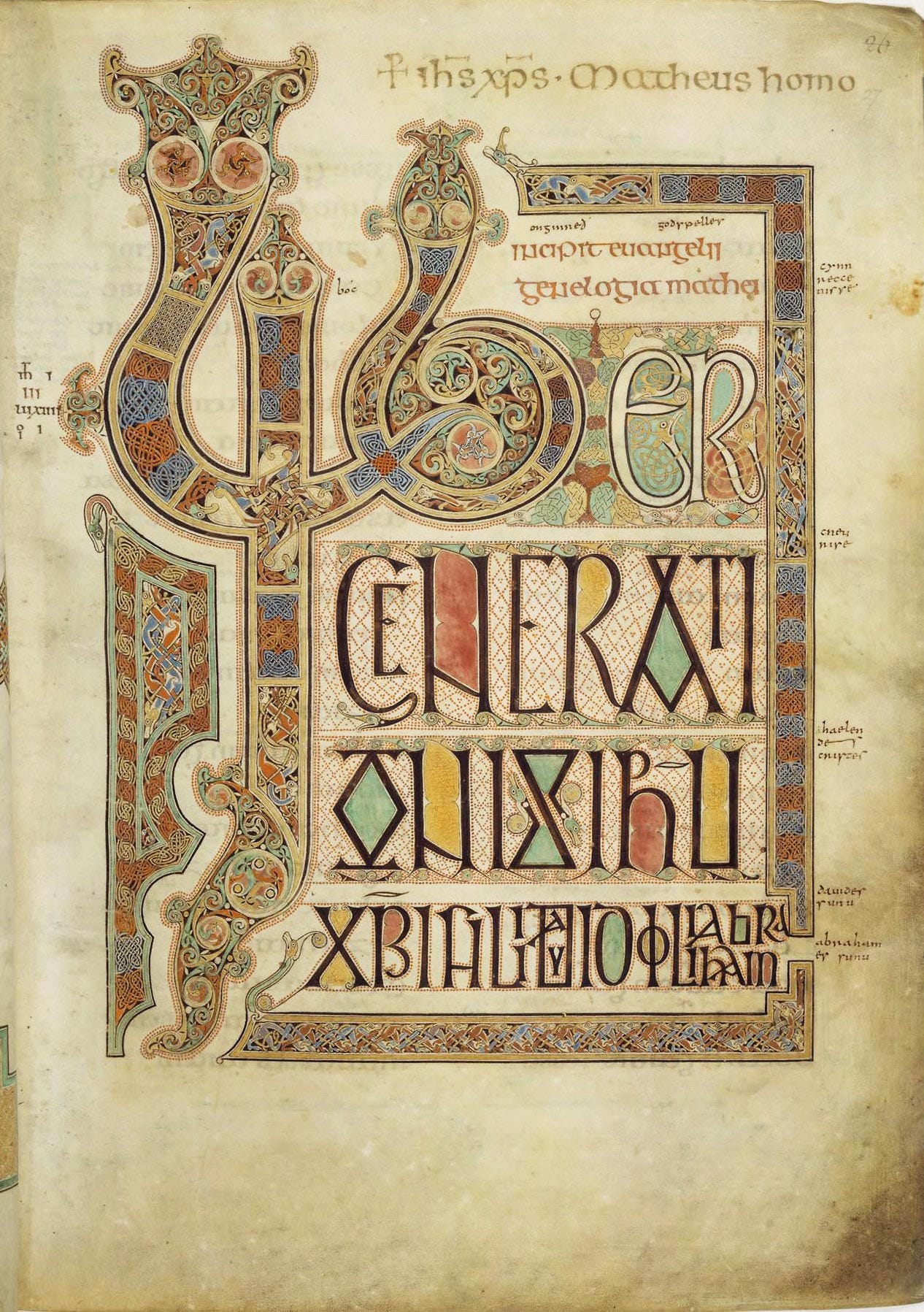

This thing, whatever it is, or was:

(The list is constructed with a little help from the people on Bluesky and has a small error tolerance; the claim is not that nobody anywhere uses these devices or forms but rather that they are essentially gone from public life, used only by eccentrics and fanatics.)

***

Like most of what we know about history, the Gutenberg revolution is a largely constructed fiction.2 Most things happen gradually, which is why you didn’t notice your iPhone taking over your life until it was far too late.

I am obsessed with physical, printed books, particularly fiction but any kind will do. I also like nonfiction, memoir, art books and photography. I love even ink and paper in their raw forms. There’s no moral valence to this passion, it’s about as honorable as loving anything; you may as well go make out with a gameboy. This love encompasses both a voracious need to regularly consume thousand-page tracts of indisputable cultural significance (Lessing, Caro, Pynchon, you get it) and a desire to print pictures of Timothee Chalamet’s face in full luminous colour and tape them up on the wall of my study (a desire I have executed, it’s for inspiration. What, now I can’t have a muse? I can’t have hobbies??) I’m poor at calligraphy and origami, but I do them. I need to stick my fingers in and on the things I love.

Maurice Sendak — Where The Wild Things Are — tells a story of sending a drawing to a young boy, a fan who had written him a fan letter, who loved the drawing so much that he ate it. Reciprocally, or inversely, Jorge the monk ate the second book of Aristotle to prevent William of Baskerville from having it at the end of the Name of the Rose. It’s entirely usual behaviour. It is possible to do this with anything. Many paths lead to many destinations — this is infinite in theory — but the proliferation in practice is actually surprisingly restrained, or at least, it can be, or at least, there is regularity here beyond what can be expected or explained. At least for now.

Printed books with paper, or some kind of paper-like substance, and ink, or an ink-like thing, will outlast every person reading this. They will outlast twitter and whatever replaces twitter; they will outlast substack and whatever replaces that. I do not feel sure whether they will outlast the internet (I think not, but let’s be frank here, that is optimism.)

Your ex has deleted your text messages. They remind them too much and too strongly of you. It’s not necessarily because they still love you at all.

And if you’re too old to have an ex who received any of your text messages, then most likely, now, you are thinking that you never will. But that’s not for certain. As long as you’re alive there are always experiences open to you. Bill Hayes fell in love with Oliver Sacks when he was 47 and Sacks was 75. He chronicles their romance in his beautiful, underrated memoir, Insomniac City.3 One can not be too sure about anything, I tell you, which first means that I tell that to myself.

What is true is well divorced from what is obvious. Like most histories, our own past, from which we extrapolate, on the plot or graph on which we make our course for the future, is also largely constructed. That does not mean there is no such thing as a true past, nor a true self — there is, but we seldom, or with difficulty, access it. One digs for it, one must dig, I am sorry. But even with that digging, we can never approach certainty. And there is nothing assured about any trajectory. In statistics this is called either non-stationarity or model uncertainty. In life this truth is so baked into the firmament that we have not yet needed to bestow it with a name.

***

Of course the other reason why we do not name something is because we would like to deny it. Sure, fine, whatever, you know that.

Last month I came across the auto-epistolary writings of Grognor (i.e. his blog)4. I was immediately distressed to find out that he is dead. I was so upset by this in fact that I realized some part of me is using posting like religion. And I think if I keep posting, then I will never die.

What am I doing here — ! Literally! I’m literally uploading a copy of myself; in an earlier piece I claimed that our writing is our work which is totally write (I swear I organically made this typo) and it is not ourselves which is also right and yet also not a single one of us really believes this even on our very best day. The reason writers and artists and everybody on the planet is so astoundingly fucking sensitive about our work is that we do perceive part of ourselves in it, we intend to use it for that, we try hard to lodge ourselves inside. Freud is on top of this (ha ha) as usual, for here is Freud’s theory of creation of the double: ‘an insurance against the extinction of the self’.5

Books are the province of lonely people. Not their-our only province, of course not, we go everywhere. But I doubt there is even the capacity to love books without there first being the experience of loneliness. I learned to love books because I could not love people, not to my own satisfaction, and they could not love me to my satisfaction either. Oftentimes or sometimes they seemed satisfied with me. But that asymmetry reflects us poorly, or I should say, reflects poorly on us both.

Nothing makes me feel my own mortality more keenly than this, whatever you’d call it, a failure or misfortune, or a lack. I have always tried and tried hard to avoid owning it. In many other ways my life is and so far has been very wonderful. I like almost all of you reading this have been spared the very worst of what life has to offer and I pray that our good fortune will continue. But to fail to find meaningful connection, or an important subset of the meaningful connections that we need, is one of the Big traumas. We are a social species. I don’t mean this in a trad way, for the nuclear family is a sickening invention, and evolutionary psychology is at best pastiche of science, but from my own life experience and observation of the primates I feel ready to call this one definitively: We are not meant to be alone. People kill themselves over less than this. I trust that you won’t ask me how I know.

To carry the burden of that sadness in more or less silence (shut up you know what I mean) is not easy and, with time, does not get easier but harder. I find life eminently, extraordinarily, excruciatingly beautiful, but life is also often unbearable, and Nicholas Spice is not lying to us when he says Bach and torture are the two poles of existence.6 There comes a time when we must ask ourselves if it is worth it — this is the point of Camus in general, the point the Myth of Sisyphus makes.7 The answer is yes, yes in general, but getting to yes here is not easy. The mark of being unserious is never having had to consider this, not even in a secondary way, on behalf of another. And there are many unserious people in our midst.

Don’t do it. There are serious people also. Not many of them, but many enough, for our purposes. Enough that some of them write blogs and books and (vomit) tweets8, and some of them get published, and some of them find readers, and even win a prize. The world is not bankrupt entirely. Good things are still possible. Good things are still here.

I often think of Toni Morrison writing at her kitchen table lonely after her kids had gone to sleep. Sometimes when people scoff at late bloomers they say you are not Toni Morrison. But how do you know? She wasn’t Toni Morrison either until she wrote the book. (Well, I guess in a sense she was, but in that sense, too, we might be.)

This is why I don’t believe there is only a male loneliness epidemic. No-one reads like women read. The unquenchable thirst for romance novels feels to me like it’s an obvious, unmistakable sign of female loneliness, or at least some kind of adjacent need that is going very deeply unaddressed and unfulfilled. And nonbinary people are also very lonely! But that would be an entirely separate post.

I’ll go so far as to believe that loneliness is organized by gender but to think that it’s the province of any type or category of person is just delusional, or lying, or an attempt to exert control over others by pretending to have access to a more important feeling than they do. (No, I don’t think everyone feels everything equally. But I am wary of the politicisation of emotion, both “female” and “male”.)9

Some of my best and sincerest friends on this earth are straight men. Because of that I know they do feel sometimes lonely. I am close friends with women and nonbinary people and so I know that they feel lonely too. I would be hard pressed to order the severity. It seems to come and go at different times.

I think that some people who love books think that the answer to loneliness is textual representation. I believe that this is incorrect. There is some value to representation, to seeing our own experience reflected in some way, but it is just as likely to mislead and isolate us as it is to uplift and reveal, and many times we will not see the difference, at least not until it is far too late.

It’s a fine, fine, fine, fine balancing act. To portray the thing that is, and to present the move beyond it.

***

I wrote this post about ten days ago, before the debate and the SCOTUS decisions. Lol.

I’ve been researching the late medieval / early modern transition in europe and bumped up against this fact several times. But if you would like to read a bit more on it, as well as many other observations, please do read Adam Smyth’s review of Bibliophobia which heavily inspired this post: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n05/adam-smyth/impossible-desires

You can read a little of the memoir here: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/26/bill-hayes-insomniac-city-my-life-with-oliver-sacks-new-york

I like this post of his the best: https://grognor.blogspot.com/2017/03/anecdotes-from-my-past.html

Quoted again by Adam Smyth, so you see I was not kidding in footnote 2. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n05/adam-smyth/impossible-desires

He describes the work of JM Coetzee: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n05/nicholas-spice/mothers-and-others

This is why I cannot dismiss Camus as an amateur or unserious as so many of the rest of you seem able to. I see my own struggle there and I know it is not amateurish. Also, this feels like a good time to say I’m not using the word serious/unserious the way De Beauvoir meant it. Sorry, she doesn’t own those words! I’m grasping for a new definition, let me cook.

I’m sorry, I’m still working all my feelings out about this (twitter).

I mean this literally, I really mean cautious. I do not mean to cloak an actual disapproval.

My god, I love the way you think. Please never stop writing.

Sharing my thoughts with you as a researcher to a fellow researcher, in the hopes that they resonate even a little: idontknowwhoneedstohearthis.substack.com

Interesting that you draw explicit a connection that I've always felt implicit regarding loneliness and being drawn to books; because in a way reading has never been more well social than before but there's a certain performativness to it all. Different ways of loving books, different ways of appreciating literature.