A guess from a guess

Translation, research, conjecture; Linear Elamite, Rumi; the position of Jupiter drives the invention of agriculture; an economist does something good

“I want to put into words but without description the existence of the cave that some time ago I painted – and I don’t know how. Only by repeating its sweet horror, cavern of terror and wonders, place of afflicted souls, winter and hell, unpredictable substratum of an evil that is inside an earth that is not fertile. I call the cave by its name and it begins to live with its miasma. I then fear myself who knows how to paint the horror, I, creature of echoing caverns that I am, and I suffocate because I am word and also its echo.”

— Clarice Lispector, Agua Viva

***

Translation is not a solved problem. Machine translation requires an enormous amount of input text to work. In 2015, when I had finally learned enough Bayesian statistics that I could have a hope of understanding in detail how Turing had deciphered enigma (these hopes were swiftly dashed) I wondered if perhaps Bayesian de-encryption methods could be possibly applied to the decipherment of Linear A, an ancient Minoan script that is thought to be a form of proto-Greek. The answer is no, because there are not enough fragments.

It turns out that if I was hoping to decipher ancient languages, I should have stayed in the humanities. In 2017, a French graduate student completing his PhD in archeology at the Sorbonne was sitting in a flat in Tehran when he noticed something unusual and interesting about a handful of photographs of inscriptions he had taken from artefacts purported to be from a Bronze-age civilisation called Elam, located in south-western Iran. The student was Francois Desset, and he was about to decipher one of the oldest writing systems on the planet, a script called Linear Elamite. (In this context, “linear” simply means “composed of lines”.)

Not bad for grad school. To understand the above, and what follows, we need to get some bearings around languages and scripts. I guess that to an advanced expert this separation will be complicated for some reason impossible to guess to the neophyte, and possibly trying to separate the two is even impossible. But we need to be aware of this much, which it is non-immediate to realise, that many languages have multiple scripts that write them, and many scripts have polyglossic uses. Hieroglyphics, for example, is not a language but a writing system for Egyptian; one of two writing systems. The other, Demotic, is also on the Rosetta Stone, which writes two languages across three different scripts — not, as it is often said, three languages. And in fact it is better to say “egyptian hieroglyphics”, for there are also Minoan hieroglyphics, that predate Linear A. (But nobody has yet deciphered those.)

The Elamite language itself is long understood because it can also be written in cuneiform, but this language is also biscriptural. The cipher in question here was its linear script.

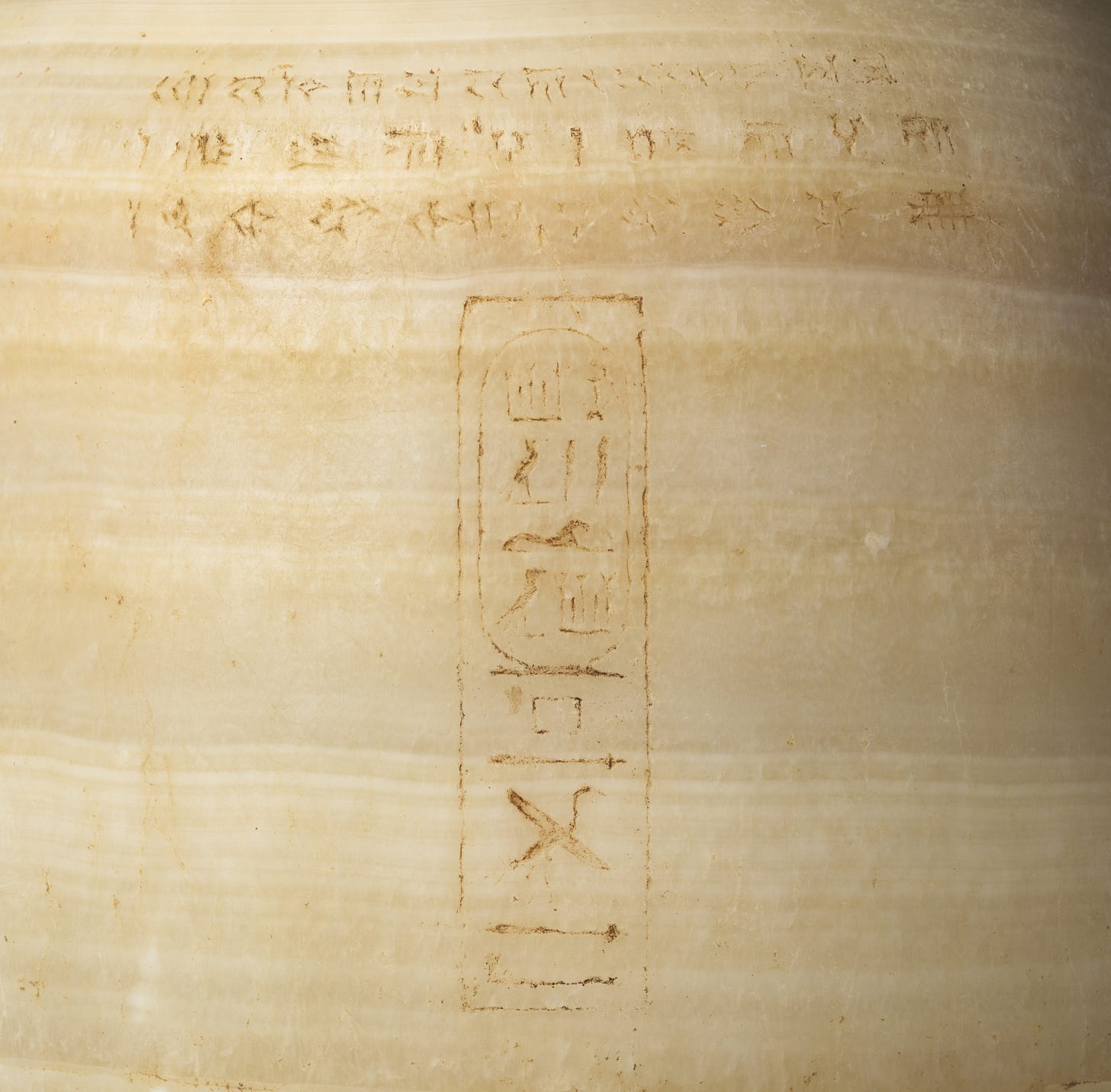

The fact that archeologists already knew how to read cuneiform Elamite meant that people already knew the names of the gods and kings of the period and region. Behold, for example, this attractive pot, with the name of Xerxes the Great King written in four languages — Egyptian, Old Persian, Elamite, and Neo-Babylonian -- using two different scripts, hieroglyphs and cuneiform, now sequestered away in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (though both of these photographs are in the public domain):

I know, it’s not that impressive. The inscription looks like nothing; you have to stare at it to even make out the heiroglyphs, the boldest of the scripts; a seated dog or lion maybe, the outstretched wings of a bird. Through time and maybe sand as if like water many things have been eroded. The real past is not captivating. It does not call at your attention. You have to choose to look at it long before you know there’s something there. Many such cases among things which are thousands or millions of years old. It takes a certain kind of moment for even one person to look.

But even if this jar, or something like it, had also featured the linear Elamite script, this probably would not have been enough. This is way too little text to work from, even for a human. Think about it. Could you decipher all English text if all you had was this to go off? You could not. But before I started thinking about this, that was not obvious, at least not to me. I have thought about it now, and it seems to me that the special thing about the Rosetta Stone is not that it contains the same text in several scripts; the jar above does that. It’s that the text it contains is long enough that it can serve as the basis for a complete linguistic translation.

There is no such text for Linear Elamite. Desset deciphered it using a guess.

That guess is the subject of this stunning LRB article by Tom Stevenson: “Beyond Mesopotamia”. Stevenson describes Desset describing the cracking stroke as follows:

“I was playing with the inscriptions and I noticed a specific sequence of four signs,” he told me. “In each case the third and fourth sign were the same.” The first sign in the sequence was believed by earlier scholars to be the sign for the syllable ‘Shi’. Desset hypothesised that if the repeating third and fourth sign were the syllable ‘Ha’, the sequence might be the name of the Elamite ruler Shilhaha. Within minutes, by fitting the signs for ‘Ha’ and the consonant L into other inscriptions, he was able to see the familiar names of gods and kings jumping out of the text.”

In the usual way of scholarship, there is of course some haggling over whether this is yet a complete translation. And obviously Desset was building on previous work. But it seems nobody doubts that extreme, almost bewildering progress has been made as a result of whatever it is Desset saw, regardless of whether he has interpreted it correctly in a linguistic sense (there is more debate about some of his downstream claims, as usual, as well).

It’s interesting to imagine this guess; this flash of insight. Almost painfully interesting. Actually, a little too interesting. It has an over-nice immediacy to it. But I think that, as in many such cases, this guess was actually the culmination of a process of previous guesses, each of which was arguably less important than the one that came before it.

If Desset had not noticed this pattern, most likely someone else would have. I know that it sounds weird to say, because the experience he had was so fantastical — or else perhaps it sounds presumptuous, because I am a mere economist etcetera. But this kind of conjecture is second nature to talented researchers of all stripes and all fields. (In fact, because I hold expertise in Bayesian stats, something most of my economics colleagues don’t, I often get to see them guess what something I am showing them means, or how it works. And they are often correct, sometimes astoundingly so. I also see the best statisticians make similar insightful leaps towards economics.)

What is less clear to me is whether we (as a people) would have got this far without one of Desset’s previous guesses, the one which seems harder to replicate, which lead to the situation in which he was even looking at these inscriptions at all. He was probably the only person on the planet looking at them with even the remotest intent to decipher them. They had been taken from a set of silver beakers locked in a vault in London, and, according to Stevenson, were widely considered to be frauds.

***

Ignorance is one thing. But it is hard to come back from false knowledge. To me, that is more impressive — that Desset wanted to see these artefacts, and moreover, that he persisted for four years in his quest to see what other researchers were relatively sure were forgeries. From 2011-2015, he tried to gain access to these beakers, called kunanki, held in private hands, and was rebuffed; Stevenson says “it took four years of cajoling”; “Desset is adamant that without the silver kunanki the decipherment would have been impossible.” The existing photographs of the objects displayed only one side of each beaker. But the inscriptions wrapped around them.

This kind of situation, where important knowledge is locked away or hidden in plain sight because the people holding it or producing the records of it don’t know what they’re seeing or looking at, is excruciatingly common.

Some of this is just our stupid choices, and that makes some frustrating sense. Like okay Indiana Jones was right, and it belongs in a museum. But aspects of this problem are natural, and ineradicable as such. (That’s the thing about nature’s laws; they can’t be broken. If you can break a law of physics, no you didn’t.) Some kind of facts or types of knowledge just are located behind barriers. This would not change even if we removed everything from all the vaults. Just because you have access to it in a literal, physical sense does not mean you have the ability to know what you are seeing.

One great barrier we face is loss of context: the obstruction we all feel against the past. So much of our history, even since the invention of writing, is gone; whatever remains is subject to selection bias. In “The Shortest History of Economics”, Andrew Leigh brings to our attention that more unequal societies where wealth was concentrated at the top were thus more able to build massive, awe-inspiring structures that stand the test of time and can compete against war and erosion. If that’s true, all being equal, such societies would be selected into the archeological record, and we would end up with a picture of our ancestors that was much more hierarchical, feudal, power-hungry and exclusionary than they-or-perhaps-we actually are.

Another great barrier is the fact, or the need of the fact, of translation itself. And an underrated part of this issue is fake or erroneous translations.

There is always an element of choice to translation. “Even” machine translation is governed by algorithmic principles that lead the engine to do things we might otherwise call making choices. Indeed these are choices, automated via higher level choices — we might as well start calling these hyperchoices — made by humans; there is no way out of this; even data-driven choices for tuning parameters are themselves set up in some or other way. I have no issue with this, I think machine translation is good; whoever set up Chrome’s auto translation, for example, tuned that thing well at least for my use-cases —

— I am not talking about that. The presence of multiple valid options and a spectrum of possible or viable interpretations and indeed approaches does not mean there is no such thing as a translation that is mendacious or false. There is. And, since we are speaking of Iran, it seems fitting to mention that no single poet has suffered more from this in the history of the anglophone world than Rumi.

If you are a normal person, then virtually every Rumi quote you have ever seen in English is a lie, a creation of one man who could not even understand Persian, the scoundrel and poet Coleman Barks, who, by the way, is still alive, making a comfortable living off that shit in Georgia.

People try to defend this as “popularising Rumi”, and nowadays you might get some limp mention of “accessibility”, but the bastardisation is so extreme that it is in fact wrong to call it popularising or accessing Rumi. The thing Barks popularised was himself and his own way of thinking. In so doing, he plunged Rumi further into dark than he had been before the “translation”. He did not make Rumi’s work more accessible — he made it less so. He hid it quite exactly where people would never find it: behind the mask of what he had pretended it to be.

Within this lies a problem with accessibility as a notion. Not everything is or ever will be accessible to everyone. That’s just a difficult fact of life, to us, for we who want to conquer everything. If you want to really know about Rumi, or Mohammed, or Ali, unfiltered through the effects of some other mind, you will have to learn to speak in Arabic or Persian.

Rumi in particular was robbed, by Barks, of his many, many substantive references to Islam, in the name of “access” for western people. An extraordinarily hostile, literally desecrating act. Do not be tricked by recent rewritings of history saying Barks only provided “interpretations”. These were and still are peddled as translations, though from the very first stanza of that poem, he has scrubbed a reference to the houris; the virgins that the faithful meet in heaven. (A better translation is in here.)

Yet even better-read and better-meaning Westerners do seem to be allergic to specifics. Even the Nicholson translation, which contains ample Islamic references, translates the famous poem of the mouse and frog — which I think are supposed to be metaphors for the body and spirit — as:

As it happened, a mouse and a faithful frog had become friends on the bank of a river. Both of them were bound to (keep) a (daily) tryst: every morning they would come into a nook, (Where) they played heart-and-soul with one another and emptied their breasts of evil (suspicious) thoughts.

But a much better, more literary, and apparently also more literal, translation of the bit that’s rendered “playing heart-and-soul” would be:

they were playing the game of backgammon of the heart.

Do western readers need to be protected from mentions of backgammon?! Or is this the influence of a foolish notion that more specificity makes poetry less good, when in fact the opposite is true? Should we go back and work this all out on the zen poets? Shall we remove their archaic references to chopping wood and drawing water? At what point, then, will it be necessary to remove any mention of the sound of bees, or the scent of the mountain pine?

I can notice also, however, that even the Nicholson — being an overall relatively accurate version — is much, much less accessible and welcoming to the modern western reader than the popular, Barkstardized poems. I don’t just mean that the Nicholson is harder to find. It is also true at the level of comprehension. If I put both in front of you (I will not, because I will not show you the Barks mouse and frog poem — it is unspeakably heinous, removes a reference to Mohammed, adds an entirely invented reference to Christ, and does not even mention the playing of any game at all), the Barks would go down much easier, which is why it’s plastered all over the internet, the clear choice of lit-it-girls and wellness influencers. Everything is a mirror to some people, or else they think it should be.

Our culture is not driven by scholars, fine, so it is. The problem is even our scholarship is not driven by scholars. The Barks translation should never have existed. That existence is not wellness culture’s fault. It is Barks’s fault and whoever enabled him. It would be better if it had never been done. It was done because scholarly people are bad, and do bad things, and have at times the most egregious of intentions. It is tempting to say a person who would do this is no true scholar, as it is certainly true that he has betrayed the principles of scholarship and translation. But how could you know this from the outside? He taught literature classes for decades. No. To know this, you have to know enough to be able to assess that very thing for yourself.

All of this is uncomfortably related to the most significant and consequential case of translation in the history of the English-speaking world: the Bible.

We think of Christianity as a white, western religion — it is that now, because we have adopted it. But this shit is not ours. Yet we have taken it on so thoroughly, and our memories are so faulty and so short, that it barely occurs to us to remember that the Bible is translated, and inevitably sometimes mistranslated. Particularly scholastic christians like to argue about the Greek, as if that were the original language of the Bible. (Edit: I have seen this done even for old testament stories, but John Quiggin points out that the new testament was originally written in Greek. Then again, this fact itself is evidence of another kind of removal on multiple levels.) Perhaps this happens because none of us wants to admit we’re not capable of beginning to think, speak, or discuss anything about Biblical Hebrew, let alone the Aramaic.

But I don’t think this is specific to religion. I mean the heteroglossia inherent to translation, and the desire to shy away from anything we do not like, and to pretend that none of this is even happening.

The history embedded in words, ideas, and things does not seem pertinent or near to us, because it does not impose itself, or announce itself as an emergency. Somehow then it does not seem to matter, just as it barely occurs to most of us to ask ourselves which translation of Chekhov or Tolstoy we are reading. We are even capable of having minor internet skirmishes over translations of Homer and that still does not translate into caring about translations of the Bible, or, say, Dante. (It’s the Hollanders’ translation. Ciardi fans, go to hell.) I somehow made it all the way through undergraduate majors in history and French without ever asking that question, and the first person I ever met who cared about versions of translations was a computer science major at MIT.

That’s why I actually like it when authors choose not to translate certain words or phrases. There is a bit of a joke about this in certain fields (psychoanalysis, anime translations, but obviously I repeat myself), but leaving difficult-to-translate terms or words au naturel has a powerful, useful function even if you do not understand them — it reminds you that languages and words have their own motley history, and that the media you are consuming comes from a substantially different context to the one in which you live.1

Including untranslated words is now considered tantamount to assuming, or in fact requiring, that your audience understands them, and is easy to deride as gatekeeping. But it’s not the translator who is gatekeeping the knowledge — the knowledge really is behind the gate, behind the barrier of the language. This is true in general. There is a specific twist on it in the case of the Linear Elamite. The language itself was trapped in the beakers; the beakers were trapped in a bank vault. People would have been, at least for some short period, arguing with each other whether these were or were not forgeries. Accessing the beakers is what resolved the argument. The argument itself was futile, while the beakers were locked in the vault.

The decision not to translate something points to the truth — if you, as I, do not know greek, then you, as I, never will read Homer. We are all forever at the mercy of the people who do, however they decide to translate it. We argue online about these translations because this sustains the illusion that we, the illiterate, have agency. In reality, we have almost none.

But not totally. Despite and even from our complete ignorance, some kinds of inroads are possible. You can use context clues and other information to discern between translations even if you don’t speak the languages; this, after all, is how we figured out half of these languages themselves. It’s important to try not to forget this, even if it does sometimes feel hubristic. Desset was armed with the names of ancient kings and the idea that something more still might be possible. Is it hubris if it works? (Maybe not, but maybe! Icarus also flew!). Not only can you have opinions and hunches and thoughts about stuff you can barely even see, it is sometimes important to have opinions and hunches and thoughts about stuff you can barely even see. How else are you going to get started?

***

Several years before Desset got his eyes on the beakers, an undergraduate student in economics from Sicily traveled to Esfahan to visit his mother who was teaching there. They then traveled to the province of Khuzestan, the seat of ancient Elam, on a sightseeing trip. That student became the economist Andrea Matranga, who from that trip has now — almost 20 years later — published a paper that seems to have solved one of the oldest and most important open problems in the history of our species: Why did our ancestors invent agriculture?

The answer turns out to be, kind of literally, because they wanted to sit down. The reason they wanted to sit down was because they wanted to store food. And the reason they wanted to store food was because, as Andrea puts it, the way you survive from one generation to the next if you’re in a very poor environment is by being incredibly mindful of the worst thing that could happen to you.

It sounds so natural. But we are talking about the neolithic. How could anyone have even remotely convincingly solved this question, and produced enough evidence to back up the theory above?

Andrea tells the story this way, if he’s asked: He began to think about this question when he was trying to photograph a ziggurat.

He noticed that it was difficult to make the picture come out well because the colour of the zigurrat was the same colour as the Earth behind it. And the reason for this is that the ziggurat is made out of mud brick from that same earth, and the bricks don’t even have to be fired, because it doesn’t rain much at all in these areas. From that, he noticed that he was standing in the ideal situation in which to build settlements. And it seems that this was the germ of the idea that it’s not agriculture that drives settlements, but settlements that drive agriculture.

Hunter-gathering, and its attendant need for nomadism in the majority of cases, has been so romanticized for us that we scarcely imagine the extraordinary pull our ancestors must have felt towards a sedentary life. I think the reason that we’re able to romanticize pre-neolithic experience is because the vast majority of us who are having these conversations not only don’t remember but can barely even conceive of a life without abundance.

Of course there is hunger in modernity. But how many academics truly feel it? And the more you feel it, the less time you have to think. This contributes to the situation that scarcity in modernity, and in our current economic systems, is still not well understood. It continues to surprise people to hear that the main issue with poverty is not the kind of crushing, grinding, average lack — although make no mistake, there is that — but rather the insane, incredible precarity, the risk of having nothing at all, that you are one tiny shock away from being homeless, from freezing or starving to death. How close you always are to the most extreme and powerful form of downside risk. But that was all of life, for hunter-gatherers. For the most part, they could not store food.

Yet somehow this garden of Eden fantasy of paradise has its hold on us. We are eager to keep it that way, maybe as a promise of escape, a notion of a thing we could return to even while we know we can’t return. We never can and wouldn't want to literally, but even emotionally and rhetorically we can't. Let’s face it: we have chosen knowledge of good and evil.2 Even in the Bible, we were chucked out of the garden. There is necessarily an end to things like simplicity and ignorance. Here we all are now in adult complexity; cynical and inventive, rococo and ornate. None of us can ever go back.

But here is an even worse secret, also from Andrea: this paradise never existed. “It was just never that good.”

The most part of nostalgia is desire, or maybe even greed. It’s something like that that sustains these illusions. It’s what we secretly want for ourselves that drives us to have these beliefs, and never to examine them closely.

I think there were actually a handful of places on earth where this abundance fantasy was realised — coastal australia, for example, and the scrubland of the karoo and kalahari, where nomadic hunter-gatherer life persisted until it was violently disrupted by the descendents of these short-ass sedentary farming cousins from the northern hemisphere who had in the meantime invented lenses, writing and guns (or, in the case of the kalahari, the bantu arrived, having domesticated wild gourds and cattle and started smelting iron).

And it is more about the northern hemisphere. The reason for that — and here we have to make at least a little concession to the wellness girlies — is the position of Jupiter.

Perhapts this sounds fantastic, but: Jupiter, the moon, and to a lesser extent several other planets, can alter not just the eccentricity of the earth's orbit but the degree and direction of our axial tilt as well.3 This creates something called Milankovich cycles, which was first figured out in a POW camp in World War I, though it took fifty years for other people to take this seriously. (No these things don't explain current warming)

We're not in a very seasonal moment, so it's difficult for us to imagine this. But 12,000 years ago, our orbit was severely elliptical, the northern hemisphere was pointed towards the sun when we were at peri-helion, and the axial tilt was more extreme. This meant that these effects were aligned in the north, creating extreme seasonality (Figure 3 of the paper: “During the Early Neolithic, these three cycles peaked simultaneously for the first time in over 100,000 years”), but were cancelling out in the south — the earth itself was closer to the sun, but these places were tilted dramatically away from it. Hence, ancestral paradise. Until 11,750 years later, when the northerners invented total war.

This story also helps explain the fact that the first several generations of neolithic peoples who started cultivating one area, storing food, trying to learn how to do the thing that became agriculture, etc, had much worse average nutrition and health than their forebears. In particular, they were shorter; they also had much more disease. The only metric of measurable improvement was a reduction in Harris lines, striations in the bones that signal long periods of quasi-starvation, which is what happens to you when you don’t have or can’t store food.

And so the reason that people (people!) switched to agriculture — despite having no idea how to do it, no experience with storage technologies, and no sense of how successful it would end up becoming — is because the experience of starvation is horrific, even if seasonal abundance means that on average you eat very well. Our ancestors were not interested in averages. They were not even interested in volatility per se. They were interested in minima; these were minimaxing agents.

Total economics cultural victory? Maybe! (Maybe not.) These are hard times in our discipline. It’s nice that one of us has figured something out.

Andrea’s theory also explains why farming spread so quickly where it did. This is for the same reason that Malthusian predictions have not come to hold: agriculture is ultra-scalable, and frequently induces additional technological change (also called “Norman Borlaug”). Hunter-gathering has the opposite structure; you actually just can't do it if you're planning to do it a lot. From my own travels I learned that even the bush reserves on which the San now live in Namibia are not large enough to fully support this strategy, not even for the few of those peoples that remain.

All this started as an undergraduate thesis! (Take heart, undergrads; he somewhat neglected his coursework. Beware, undergrads: it took him 20 years.) Andrea describes the process of the project as having a “Forrest Gump” aspect, where he built on each step, generating conjectures on top of each other. This made me think of Polya's phrase in the introduction to “Mathematics and Plausible Reasoning”, a bit that I had written down: “A guess from a guess”.

I thought it was about this kind of chain of plausible logic, but when I went back to the quotation, I saw that I was wrong. In fact Polya was describing the need to make distinctions between more and less reasonable guesses.

The difficult thing about all this kind of business is exactly that — you don’t know if you’re being reasonable, sometimes it takes you years, many years, to be sure, and that’s just you, not even convincing others. I asked Andrea about the role that guessing had played in this work. He said he had come to think this was a strand that runs centrally through research: “How do you find a balance between creative speculation and going overboard into "aliens built the pyramids" territory?”

It seems to me that he found the balance extremely well, as did many of his predecessors, who did the work who set up that trajectory. When I put this to him, he was much more modest: he thought he was right, yet also saw himself as offering a story about the past that was part of a long tradition of acute psychological projection. He made a self-effacing joke that I think for all his achievement he still thinks is just a little bit true: “There’s no such thing as history, it’s current politics in period costume.”

***

He’s probably right that it’s not a coincidence that an economist in the early 21st century would naturally look to volatility as an explanation for a human pattern. But (I know he knows this) that doesn’t mean it’s wrong. Our experience may make us biased in what we look for, but that doesn’t mean it corrupts what we see when we look. Imagine looking at a picture that is printed in full colour, but you can only see red. You would not be wrong about what you see, it’s just that your view is incomplete. If you get enough people looking at it who see enough different colours, eventually you could reassemble the picture.

That’s always how you have to think about scholarship, including the most technical, rigorous science; including pure mathematics. I’m sure we all know this. (Man I hope we all fucking know this.) On the other hand, we don’t typically act as if this is true — or is it that we do act as if it is true too much, that the process can or has to be trusted no matter how stupid it is? And if that’s the case, can we stop it, and do something else? Will science look like this 100 years from now, or 2000, or 2 million? Is there an alternative to the familiar “trust the process” attitude that one has to take to science and scholarship or else one will go mad?

I actually do think not, and yet — as Andrea says — there is something Q-anon about this — I feel it too. No other topic makes me so sorely tempted to channel my inner Malcolm Gladwell, which is about as close as I get to Q-Anon, with the loose attitude to facts and near-religious faith in excitement as a measure of progress and correctness.

People’s excitement is truly unreliable.4 People claim to care a lot about the neo- and paleolithic. But then Andrea’s research has attracted much less attention than it should, except among the academic podcasts. This is the most important economics paper of the past 25 years; maybe ever, the only comparable achievements that spring to mind are the market for lemons and Arrow’s impossibility theorem. I wouldn’t presume to know how Andrea feels about the reaction but I personally feel like yelling ISN’T ANYONE ELSE SEEING THIS?

I’m not saying that excitement is wrong or insignificant. But it has to be interpreted carefully. It is not a clean signal of what exactly is important. People care about the paleolithic period and our ancestral humans very deeply, but, I think, for the wrong reasons. They-slash-we care about neolithic humans only because they are an extremely powerful source of input to the most cherished area of our imaginations — the part of us that romanticises the act of survival as being an inherent form of innocence.

The idea seems to be that there is no evil that close to nature.5 The other animals are not evil, are they? (They are! Orca, Chimps, etc are as sociopathic as us.) We project our best selves onto these unknown people and places because we want the fantasy of being better, of anything better than this. But this dumb bullshit only works because things are so vague. We don’t want research about the neolithic even if it is stunning and true because we actually want to preserve our ignorance, to use it as the garden of our fantasies. We do not want to know that although hunter-gatherers survived, and they were even healthy, their lives were miserable and tense. That kind of research punctures the fantasy, and the truth is a slim consolation.

More cerebral, more elaborate kinds of survival — if indeed settlement and crop-growing are that — are no less close to nature. In fact, since we out-competed the hunter-gatherers, in a sense, it might be that we were “more” aligned with the natural environment. But that does not make us inherently better or good, any more than the paleolithic was a better thing than the time that came before it. The desire or plan to obtain some ascent to grace is as delusionally self-flattering as the notion of the fall. Andrea says: “It was always some shit or other! We’re always in the middle of something.”

People are always having ideas towards improvement, and guessing towards what they want to learn. When I opened up that topic, Andrea made the point to me that research is not about having ideas, but about making the ideas “impossible to ignore.” (This is not a given, in fact, and seems to be somehow harder and harder the more true the damn idea is.) He expanded on this: that there is an intersection between being right and being scientific, but that they are not the same thing. There is a distinction between ideas being useful or scientific, and ideas being true. Of course, in academia, we hope that ideas that are truer bubble up; but that is a hope.

People do not always bubble up to the surface either. What strikes me about Andrea and about Francois Desset is how precarious their positions were, that they put all their energy into these ideas while they were still students; that they were willing to work on this stuff for years. I think that this is actually why they succeeded, but they could have easily failed. It’s a shame that people like these are so rare in academia. But of course, they are anti-selected.

Most of us will never do anything as impressive as either of these researchers. On the other hand, maybe we don’t need to. Most scholarship, good or bad, for well or ill, proceeds by incrementals. And I think, or I hope, this means we will also never do anything as terrible as Coleman Barks. It is, I think, just like Andrea says. I have grappled with this myself in the course of trying to propagate Bayesianism into applied micro.6 If you take up the mantle of influencing anything, you have to know that you may influence things wrong. That risk is always present. It is pleasant to pretend this isn’t an issue, and doesn’t matter, but of course it is and it does. You might say you couldn’t have known, but often you could have. What we know, even about ourselves, is not a matter of intelligence, but of dedication and persistence. Some of us seem to feel this a lot more keenly than others.

The world would feel less tragic if we were all delusional. But the truth is some of us achieve understanding and some of us don’t. And this is true on any given issue, but also aggregates upwards, so that one is living a more or less ignorant life. If everyone were equally, or roughly equally, delusional on average, this would not be such an issue. Our confusion would not feel abject, and instead would be a kind of communion. The reality is much more painful: understanding is very possible, it just is never assured.

Bad guesses are dangerous because they displace good guesses. False knowledge is dangerous because it displaces the truth, which is in fact possible to access. If there were no passage out of ignorance, bad guesses would not be tragic. Of course we have to accept the possibility of bad guesses, to make any guesses at all. But that does not make them less bad.

Pretending that no relief from ignorance is possible feels good because it resolves or indeed itself relieves the internal demand for discernment. (This is the same reason that forming the judgement “being judgmental is bad” feels so good.) It is very pleasurable to pretend that since we will never know for sure on many of these questions, there can never be any updating; that there is nothing between proof and ignorance. But all of life proceeds between these poles. The implacable demand that we navigate that terrain creates inside of us a lot of tension, but it is never going to go away. It is present in every field, in every area, from romantic life all the way to mathematics.

In fact it’s more central in math. Conjecture is the main form of the art. It’s not like anybody ever found, or is going to hand you, a codex to translate between math and English. All learning, in mathematics, involves some type of guess — Polya actually made some attempts to formalise this kind of proceeding. That is the point of “Mathematics and Plausible Reasoning,” summed up in this pedagogic thesis: “Let us teach proving, by all means, but let us also teach guessing.” He says that in fact there is a method. But you have to read the whole book to get it; or to even know if there is something to get.

It’s ten years since I last looked, but Linear A still has not been deciphered. There are, as always, a few cranks on the internet who think they have managed it, and who have not yet managed to distinguish a guess from a guess.

***

Actually the real joke is when they don’t do it in anime translations, like when Pokemon dubbed onigiri “jelly donuts”, as if anglophone audiences, having handled 150 new words for Pokemon, would nevertheless have their heads blown off introducing the concept of rice balls.

It actually strikes me now that this is a decent metaphor for consciousness. I’m sure someone else has written about this.

When Andrea was helping me proofread this, to make sure I don’t sound like a dumbass (well, we tried), he commented on how the foundational work in astronomy and mathematics that allowed human beings to discover these facts about the orbits was itself religiously motivated, in a sense: “the work of Laplace and Lagrange was partly a way to kick out God from orbital mechanics”, as he put it. (!!!)

I WROTE THIS ALL BEFORE THE MIT FRAUD SCANDAL

Thus evil as a form of decadence… there is a fascist overtone.

This is my chosen form of agriculture.

Averages are useful things yet managing to averages can kill you.

Agriculture is selling a producer collar where you give away some upside to get higher floor protection.

Pretty smart idea.

Very interesting. I'm working on translation in a very technical decision-theoretic sense: how do we relate state-space models of the world expressed in different languages.

But I thought, and a quick search appears to confirm as a majority view, that the (New Testament) gospels were originally written in Greek. That would make sense to me given that Christianity had spread widely by the time they were written, on most accounts.