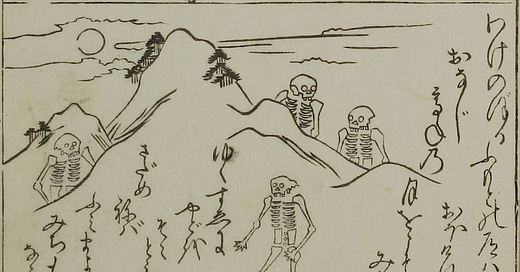

“Then the ghosts of the dead swarmed out of Erebus – brides, and young men yet unwed, old men worn out with toil, girls once vibrant and still new to grief, and ranks of warriors slain in battle, showing their wounds from bronze-tipped spears, their armour stained with blood. Round the pit from every side the crowd thronged, with strange cries, and I turned pale with fear.” — The Odyssey, Book 11, A.S. Kline’s translation

***

2023 was the year I quit. I really didn’t want to write this essay and it’s probably too early — perhaps that just means we won’t get all of it out of me, or maybe you just won’t get to read all of it yet. (Despite what you may imagine, I do, in fact, edit these posts.) I’m also wary of even going close to any sort of confessional essay, because it’s hard to talk about quitting without falling into the trap of explaining yourself, and that is not my intention. Quitting is just as natural and good as not quitting, but people don’t ask you too often why you don’t quit.

Still, I guess in some way I want to mark the occasion, and to talk about coming home.

So, yes, I quit my job in the ultra-halls of the super-elite of academia and came down off the mountain to a more modest life on its slopes. This is actually not as uncommon as people seem to think it is, but I’ll concede, it is not entirely usual.1 I quit a fair few other things as well which I definitely am not going to tell you about, although you do all know about one of them, because this year I even quit being a woman. And believe me there are many more, even more terrible and profoundly life-changing decisions than even that, which I have made this past year. If you’re feeling discombobulated about this or me or where this essay is going, I don’t blame you. I barely know what’s going on myself.

It’s a strange place to find yourself at 35, a week shy of 36 now. You’re supposed to grow up and know yourself, but in fact, that isn’t how it happens. Genuine self-knowledge is a gradual process and every incremental inroad takes a lot of work. And the work is intricate and subtle, with the necessary development of particular skills. It’s a skill to inquire into yourself and into others. It’s a skill to probe reality without disturbing it one moment before it needs to be disturbed, which is necessary to study it. It’s a skill to first tolerate, then accept, and then finally welcome your own emotions, since this often feels scary and revolting. And all this, and more, one usually is not taught.

Instead, one first learns bad ways of doing things, typically from one’s parents but also from mentors and broader society. And so then, as in the apocryphal story of the zen master telling the student that if he is going to learn anything or receive any wisdom he will first have to empty his cup of his preconceived notions, the task is not so much learning but unlearning.2 It is not so much that one strives valiantly to come to the heart of oneself. The work primarily involves the destruction of the thing in the way, the thing you think you ought to be, the false self that bars the door.

For all our talk about growth and authenticity, and despite the sustained efforts of Douglas Winnicott, bell hooks and Brene Brown to help, the road before us is long. I think we still do not have the cultural language necessary to properly discuss the matters at hand. It’s still somewhat common for people to believe firstly that there is no such thing as a real self, and secondly that any false self we have constructed is just as good as any purported real self could be anyway, when firstly, yes there is, and secondly, no it isn’t.

In fact I can tell you how I learned for sure that there is such a thing as a real and authentic self: I learned that it is possible to betray it.

***

It is at the moment that one starts to wade out into these waters that one starts to understand the function of myth. There are things so complex and emotionally demanding that it is not possible to speak about them, certainly not in direct terms or in a mode we would recognise as discursive. I actually was late to this realisation, and didn’t see that this was true until I began to seriously meditate, during grad school, at the Greater Boston Zen Center.3 But even at that time I did not fully understand how serious that stuff was, how much of our selves it contains, and how important and difficult it is to access and then parse it. Attempting to express ourselves, even to ourselves, is the mother of all translation.

I don’t think it’s a surprise, then, that we are still entirely capable of having a culture war about Homer.4 The Odyssey is a particularly great example of the enormity of this problem, at least to us, because the very first line contains a word to describe Odysseus that is untranslatable into english.

I am told — by a variety of sources — that the literal rendering would be “of many facets” or “of many turns” or perhaps “of many devices”. None of these are natural or idiomatic in English. Kline’s translation, which you can read for free online and which I like in general, begins “Tell me, Muse, of that man of many resources”. This is okay, but a little clunky and timorous; it ultimately doesn’t satisfy. Fagles calls him “The man of twists and turns”; this is also no good. Wilson flings the line out much more strongly:

“Tell me about a complicated man.”

What’s so striking about this, and about the Odyssey in general, is that it is powerful despite how profoundly mundane and limited it is as a set of concerns.5 This is practically arthouse cinema. Getting back home? Who the fuck cares about getting back home? As an impetus, it’s quite boring. That shit only hits you like a tonne of bricks after you turn 30 or maybe if you’re late to it 35. And so I think the word “complicated” here is an inspired choice. When one is young, one dreams of being complicated; when one is older, one dreads it. But like it or not, our lives are complicated, and we all become complicated through them. And I think that’s the best case scenario.

My favourite moment in the Odyssey is when our hero speaks to the dead. He has to do this in order to get home, which might be the earliest possible literary endorsement of psychotherapy, or at least of dredging up the past. More precisely, he has to speak to the sage Teiresias — who, incidentally, lives some years of his life as a woman, and is perhaps most famous for outraging Hera by insisting women get ten times more joy from sex — but in the process he also sees lots of dead people, including Agamemnon, Achilles, and also, his own mother. He does not even realise she has passed when he summons her, so distant has he grown from his own life.

The mere idea of having to summon the dead to get directions and then being forced to unexpectedly confront the ghost of your own mother, whom you had not even realised was dead, is a pretty precise encapsulation of the awkward places it is possible to find yourself midlife. Also, Odysseus’s mother does not recognise him! He wonders why that is, and Teiresias says it is because all shades have to drink the sacrificial blood in order to see him, in some sense, and she can only do that if Odysseus lets her. But even after she can see and speak to him, he remains uneasy and unsure of her. He even wonders if Persephone has sent some impersonation of his mother to torment him.

Odysseus weeps and trembles pretty often throughout his story, as anyone in midlife ought to. Modern audiences accustomed to more stoic male portrayals would probably find this refreshing — if they’d actually fucking read it, but nobody reads anything, etc. He summons the dead himself, at great personal cost, and still he fears them. But why not? He only summons them because he’s desperate. The ghost of Achilles even says so, in fact I think a modern parsing of his opening lines to Odysseus would be something along the lines of “Son of Laertes, you must be desperate…”

Achilles himself is such an interesting character, the quintessential angry bisexual, the blueprint, the man who had the chance to live a long life and be forgotten, or die young in a blaze of glory and be remembered for ever. We know what he chose — we’re the ones who remember him. But we remember him for his weakness and his rage. The body part we named after him is not the bicep but the heel. You don’t get to choose how people remember you. That’s one pretty good lesson from the Greeks.

Odysseus asks Achilles what’s so bad about being in the underworld, really — if you died a hero, and thereby get to be of high status there, enshrined as a judge and remembered as glorious by everybody everywhere for ever. Specifically, in the Kline translation, he says this (emphasis mine):

“Achilles, son of Peleus, greatest of Achaean warriors, I came to find Teiresias, to see if he would show me the way to reach rocky Ithaca. I have not yet touched Achaea, not set foot in my own land, but have suffered endless troubles, yet no man has been more blessed than you, Achilles, nor will be in time to come, since we Argives considered you a god while you lived, and now you rule, a power, among the un-living. Do not grieve, then, Achilles, at your death.”

Swiftly, Achilles replies:

“Glorious Odysseus: don’t try to reconcile me to my dying. I’d rather serve as another man’s labourer, as a poor peasant without land, and be alive on Earth, than be lord of all the lifeless dead. Give me news of my son, instead. Did he follow me to war, and become a leader? Tell me, too, what you know of noble Peleus. Is he honoured still among the Myrmidons, or because old age ties him hand and foot do Hellas and Phthia fail to honour him. I am no longer up there in the sunlight to help him with that strength I had on Troy’s wide plain, where I killed the flower of their host to defend the Argives. If I could only return strong to my father’s house, for a single hour, I would give those who abuse him and his honour cause to regret the power of my invincible hands.”

The first part of this answer is even more powerfully emotional than we understand it to be, because we are less obsessed with status than the ancient greeks were. To say that it would be better to be a poor peasant without land, another man’s labourer — or, as this is otherwise often translated, a serf, a slave, a servant or a dirt-poor tenant farmer — is to be the absolute lowest of the low in the ancient greek estimation.6 Nothing is more ignoble and deplorable. For Achilles, the great Achilles, immortalised and reigning in hell, to say this to Odysseus, is shocking. It’s as if he has taken two fists of Odysseus’s tunic and is shouting at him “Forget glory, don’t be an idiot — live, damn it, live!”

It barely requires reading between the lines to understand the most confronting thing about Achilles’ story, about his choice to give up his mortal life and die in a blaze of glory, which is that he regrets it. If he could go back, he would make a different choice.

***

It’s not that rewards and glory and status are bad, they’re not bad. They’re just not as good as living, and should not be traded for it.

I think there are people among us who don’t realise even the distinction here, who don’t see the difference between being successful and being personally fulfilled, who can’t conceive of private happiness, outside or quite separate from attaining fame or status or whatever. It doesn’t have to be fame or status actually. It can even be a particular identity. A lot of people are driving themselves into misery clawing for the identity of “progressive” or “enlightened” or “artist” or “writer” or “good parent” or “good daughter” or “wife” or even just “woman”/“man”; “boy”/”girl”, rather than surrender to life and the truth. And it’s this stuff that really makes up the false self.

Judith Butler puts it very well in Gender Trouble: “To what extent is “identity” a normative ideal rather than a descriptive feature of experience?” It’s good to pose this as a question — almost all koans are posed that way. But there’s a reason why koan practice is conducted almost entirely in privacy, if not in secret. To nurture this unfurling of the genuine experience takes patience and requires a lot of trust and help. It’s easy to get discouraged, or indeed to never start. It’s easy to dismiss this stuff as hogwash.

The choice between breathing life into the true self versus clinging to this desperate illusion can become surprisingly stark at certain times in life; in certain relationships, or certain contexts. It’s hard to speak about these things. It’s deeply personal. And once you get some glory or status, or attain some particular cherished selfhood — even perhaps incidentally or without seeking it — you get married, you get successful, whatever it is — you think it will make things easier. But in fact you don’t really know how it will affect you. Such things have hidden costs, and unintended consequences.

I think in general we need to be in environments that support this kind of growth and self-knowledge, at least for ourselves or as far as we understand it. I used to pride myself on being able to do it no matter how hostile the social environment. That’s denial, obviously, but also I now think that even wanting to be that strong and powerful is itself just utter bullshit. And I do think that the specific thing that academics, artists and writers in particular have to worry about and need help avoiding is the thing Achilles warns Odysseus against: destroying your life out of an aspiration to glory.

And that destruction can be subtle. This problem is worse higher up the chain — as you become more famous and successful — but the correlation is weaker than you might think. There are lots of ordinary people bartering their life away for this, continually hoping to be rescued from what they view as obscurity by their next big idea.

To aspire to a glory so profound and overwhelming that it is equivalent to immortality is to aspire to climb Mount Olympus and become a god — and so the thing we are discussing here is hubris, a crime against fortune, a mortal sin, a mistake you can’t come back from. The ancient greeks tried to deliver themselves and us this lesson, they left us this as well as many other things, but we read “Zeus will strike you with thunderbolts if you try to climb to the top of the mountain” as if it was a superstition held by idiots rather than a warning from our ancestors.

I don’t think ambition is bad, and certainly neither did the greeks. Ambition is very excellent, but ambition to what? To do or make something great, or to become immortalised as a great thing yourself? The latter is sick and dangerous, an annihilating denial of who and what we really are, and on some level I suspect we all know it and feel foolish about wanting it and deny that this is in fact the thing we want. But it can be difficult to remember that you’re supposed to deny it when you’re talking with the great Achilles, or when you seem to get within striking distance of the thing. Achilles does the right thing and corrects Odysseus. Most of the murdered souls you can meet with are not as charitable as this.

We live in a different age with different mortal sins that imperil us for the most part, and we struggle to read these stories well because of that. It may even seem paradoxical to us that the greeks were so concerned with hubris when they were at the same time so astoundingly obsessed with status, but it ought not to be surprising — the status obsession is what produces the sin of hubris in the first place, and the resulting need to tell the stories that try hard to stamp it out.

Our own obsession as a broad culture is not status but industriousness, or productivity. The flaw that this has fostered is distraction. It sounds humorous, probably, just as the notion of “excessive pride in glory” would have sounded humorous to your average greek, but distraction is no joke. Our time on earth is the most valuable thing any of us has, and frittering it away is evil. Knowing yourself and the character of your life takes up a lot of this time. You can’t even afford many other serious pursuits, let alone distractions.7

Look at what Achilles mourns for. It’s ordinary life, and most of us are missing it. To snatch it back is the triumph of the Odyssey. But the paradox of ordinary life is that we do not enjoy it. Most of us, at every social stratum, are outright looking for escape. It’s not populist or anti-elitist to valorise the ordinary. Glory and power is populist; blockbuster movies are about geniuses and superheroes, our own modern denial of death. A sustained or cultatived interest in the mundane is actually a little pretentious, a little wanky. Only arthouse movies, literary fiction and zen buddhism are prepared to admit to trying to tackle ordinary life, and most of the purveyors of these things aren’t even very good at doing it. It’s actually hard to even make a real attempt, let alone to have any kind of success with it.

So I have to admit I was a little surprised when I discovered how badly I wanted it; how much I wanted to return home, or at least to try to, even if only to and for myself.

As a goal, it feels foolish. If you’ve studied Odysseus, you know that nothing all that good is waiting for you, not really. Or actually, it is good, it’s just that the journey is horrific, and you have to tear yourself from the embrace of the goddess, and nearly be drowned in the sea, then raise the dead and ask their ghosts for counsel, and witness the torment and slaughter of your comrades, and then when you actually get there you have to fight even more, even harder, and nobody sings any fucking songs about you, not now and not until the end of time or the heat death of the universe, and if they did the only thing you’ve done that’s worth being remembered for is finally returning home.

But that doesn’t matter. On the slopes of the mountain, someone is chopping wood and boiling water for tea. It is better to serve on earth than to rule in Hades.

***

To be clear, what I’m describing is voluntarily leaving an elite economics department for a very good but non-elite one. People sometimes act as if this is unthinkable or unheard of, but it actually happens with some regularity.

This zen story, also called “Nan-in pours the tea” is very, very good, but it is not old, and it is only a classic in the west. In fact it was probably invented specifically for us, to chastise us for thinking that we know about Zen before we even sit down to practice it for any real period of time. I have wondered about its shifty origins for years, and finally stumbled across this post by Lajos Brons confirming my suspicion.

And I had done a lot of therapy!!! Somehow this had not sunk in??? Why are we so dumb in our 20s!

I refer of course mostly to unqualified men on twitter periodically objecting to a professor of classics named Emily Wilson translating The Odyssey, acting as if she has personally snatched the Fagles out of their children’s mouths.

I have not read Ulysses, but based on the way people talk about that book it seems likely to me that Joyce understood this.

This view, along with much of my views about the ancient greek world in general, is due to Donald Kagan. His entire Yale course on this topic is on youtube and I think I have watched it 15-20 times in the last ten years. If you watch this series you should skip his introduction in lecture 1 — it is mostly vague attempts to claim that western civilisation is the best thing ever and that everybody wants to be us (lol) — but lecture 2 onwards is outstanding.

I am not talking about rest, which is obviously crucial to the whole process I’m vaguely suggesting or describing or backhandedly recommending to you. I’m talking about busy work, or chasing things which don’t matter, which is most things.

"What grace you give your words, and what good sense within! You have told your story with all a singer’s skill" - King Alcinous said to Odysseus.

Rachael, wishing you so much love and fulfilment!

The overwhelming majority of people tend to follow the herd, pursuing what's established and expected. They don't necessarily consciously reflect on what makes them happy, let alone pursue the road less travelled. I am so so happy that you are doing what makes you happy.

Brava xxx

Yours is the only Substack where I make sure to never miss an article; this one really knocked me over. So much you wrote is resonant with things I’m thinking about right now.

This in particular will stick with me

“It’s still somewhat common for people to believe firstly that there is no such thing as a real self, and secondly that any false self we have constructed is just as good as any purported real self could be anyway, when firstly, yes there is, and secondly, no it isn’t.

In fact I can tell you how I learned for sure that there is such a thing as a real and authentic self: I learned that it is possible to betray it.”

Thank you and good luck <3